Wildlife conservation means different things to different people. What are we protecting? And why? Without tackling these questions, we are unlikely to achieve our goals – even conservationists will work against each other.

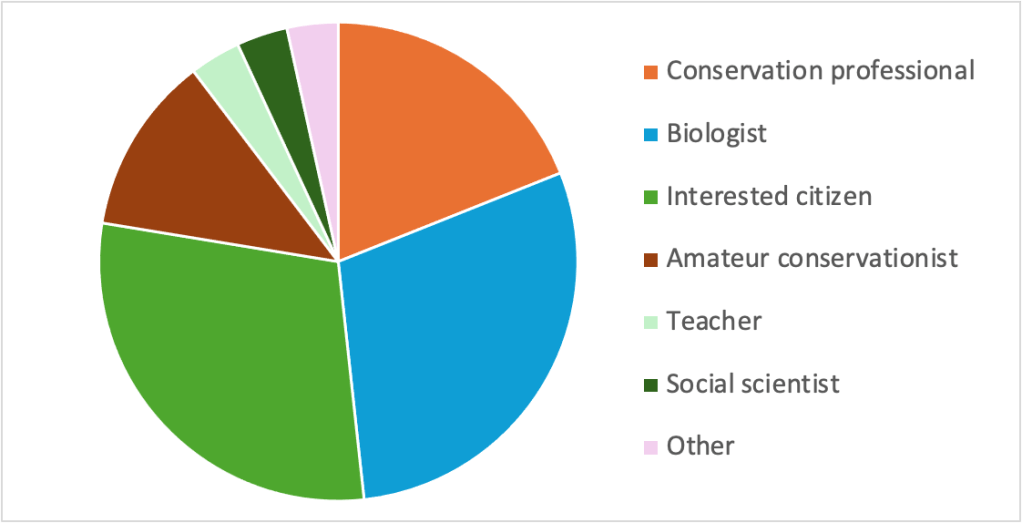

To help me understand how people view conservation, I ran a short survey. Thank you very much to everyone who filled it in – I have found your responses fascinating, and have gained valuable insights. I’ve shared some of them below.

I should be clear that the survey is by no means comprehensive or representative. It was answered by people who saw it in my social media feeds, so no doubt many perspectives are missing. Despite these caveats, I still think the answers are useful. They highlight the diversity of views, and encourage us to interrogate our own views. Most of all, I hope they will spark conversation.

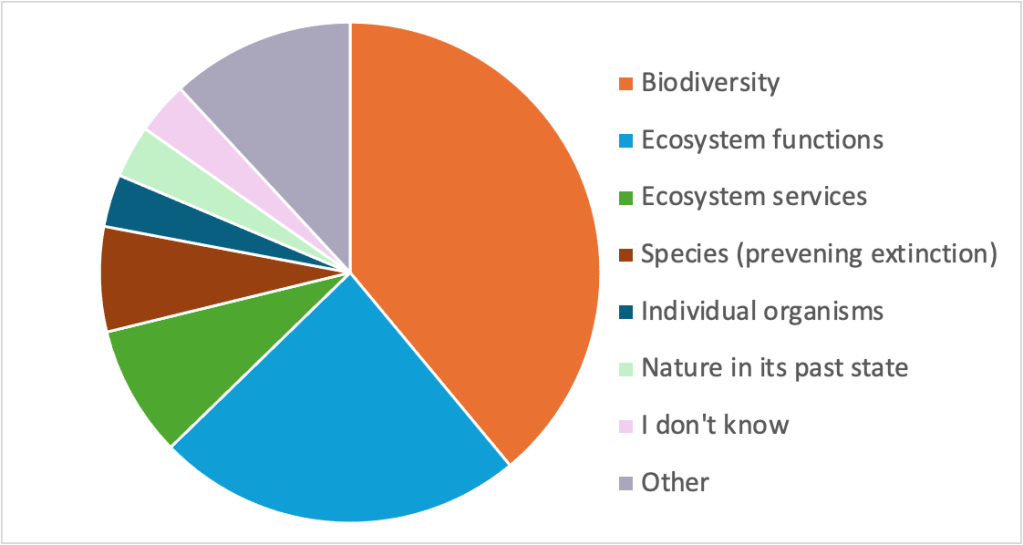

What should conservation primarily aim to protect?

The most common answer was biodiversity (represented in orange), followed by ecosystem functions (pale blue). These functions include flows of energy and nutrients through food webs – they represent the actions that organisms perform (such as pollination), rather than the organisms themselves.

Anyone who ticked ‘other’ was able to add a comment. These comments included protecting the ‘beauty and diversity of nature’ and reversing ‘the harms we’ve done’. Multiple comments reflected the belief that these different goals aren’t in conflict (something that I’ll come back to).

To me, there were surprisingly few votes for ecosystem services (benefits to humans). This is a striking contrast to many common narratives about protecting nature, particularly those coming from governments and policy makers. Many environmental charities and academics likewise focus on ecosystem services.

Overall, these results show a fascinating discrepancy between different people’s views, and between the views expressed here and common narratives about protecting nature. These results also don’t match my interpretation of the philosophy of environmental ethics. Most people are placing value at the level of biodiversity or ecosystem functions, whereas I place it at the level of individual sentient beings, including humans.

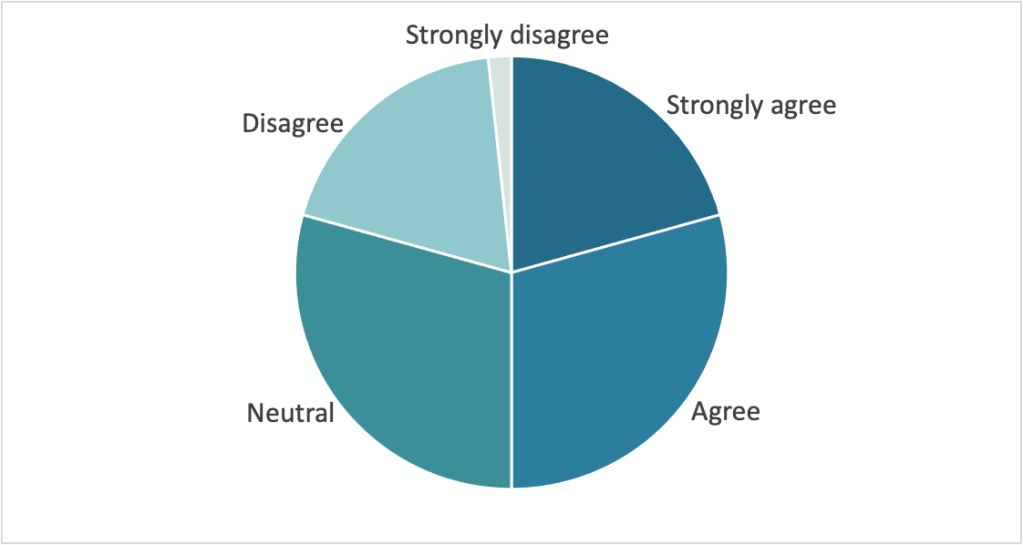

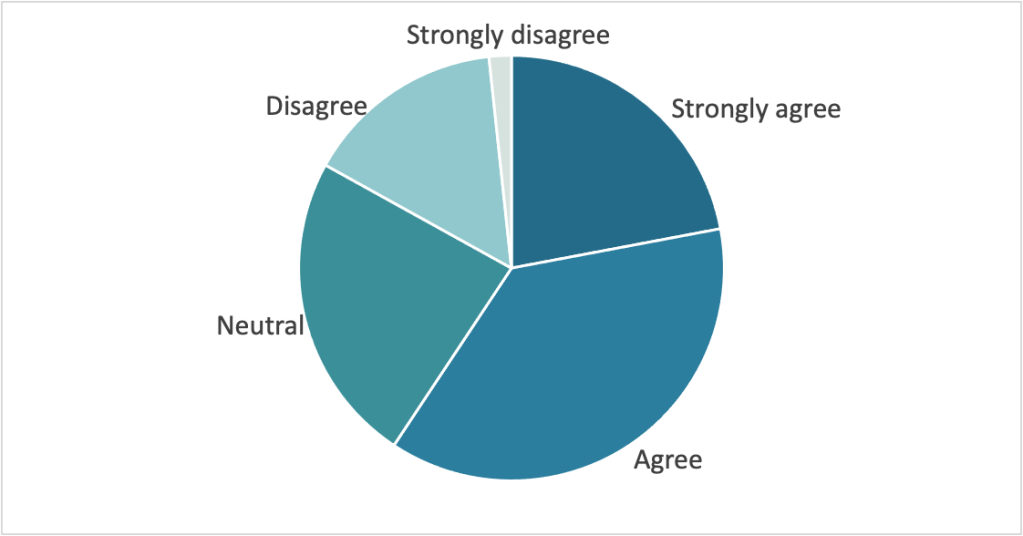

Nature conservation must never violate human rights

About half of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that conservation must never violate human rights, and the number of people selecting ‘neutral’ suggests a level of uncertainty. This was reflected in the comments section.

Many people highlighted the lack of clarity about what counts as a human right, which would affect their answer. Multiple comments stated that nature conservation will impinge on capitalism/profit making. Other comments gave specific examples of rights that shouldn’t be protected, including riding your horse, walking your dog and “what rich people want to do”.

Comments in support of protecting human rights mentioned marginalised communities, and the importance of rights such as access to food and water. Sensitivity and equity were highlighted.

Multiple people commented that they didn’t know why conservation would violate human rights. High-profile examples include the forced eviction of people from land that has been designated as protected area. Burning dwellings is all too common a strategy, and there are examples of people being killed when they tried to resist eviction.

Equally, there are times when protecting nature and protecting human rights go hand-in-hand. As one comment pointed out, conservation can often benefit from ensuring Indigenous peoples have rights to their land.

The website Mongabay has lots of interesting articles about conservation and human rights, with examples both of synergies and violations.

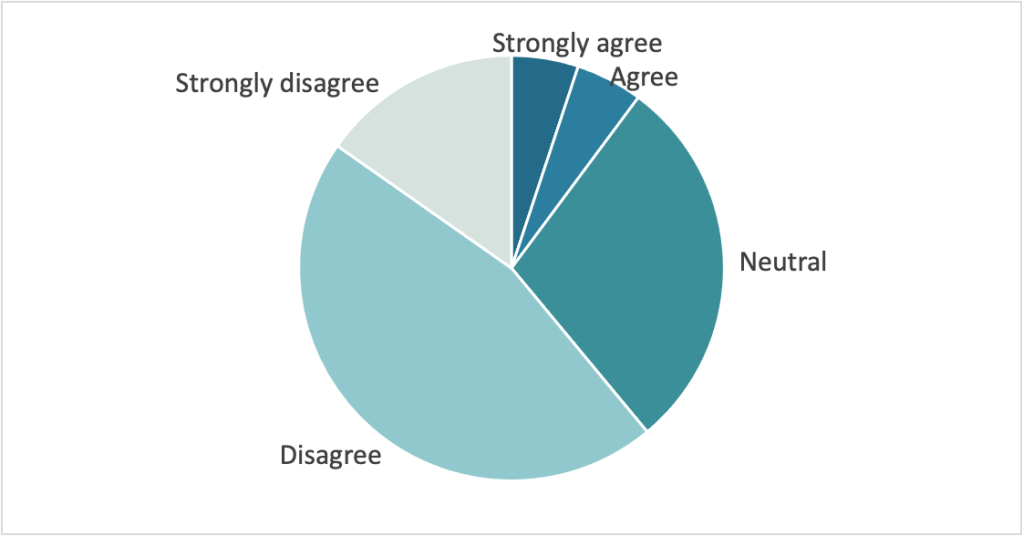

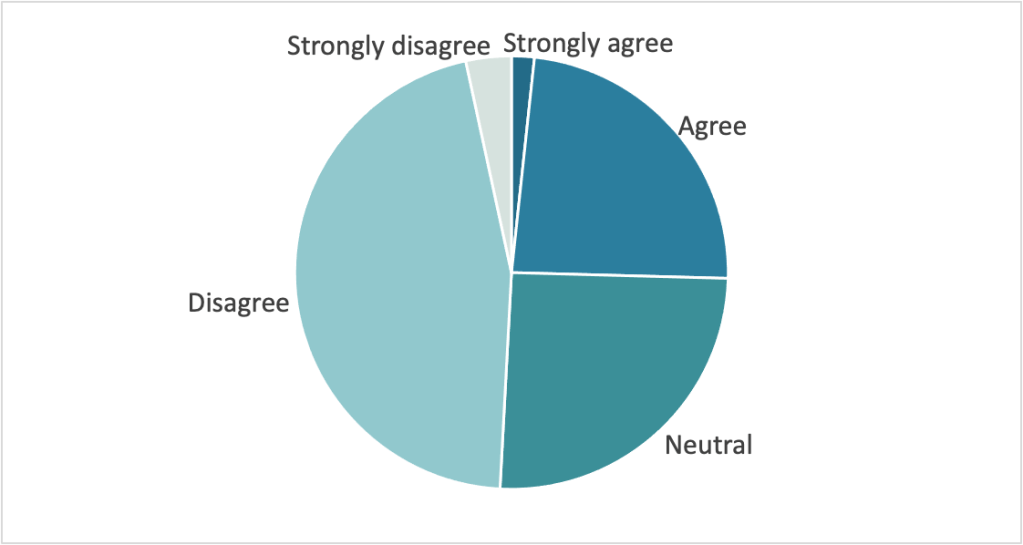

Benefits to humans should take priority over biodiversity

Of all the questions, this had perhaps the biggest agreement among responders. Only about 10% of people agreed or strongly agreed that benefits to humans should take priority over biodiversity. The comments also showed a high level of agreement.

Many commenters shared their belief that biodiversity benefits humans, meaning there isn’t a conflict between biodiversity and human wellbeing. One person speculated that we don’t put money into creating solutions that can bring both human and biodiversity benefits.

People also commented on the uncertainty surrounding the risks of losing biodiversity, and what impact that could have on humans in the long-run.

People again pointed out the need to define benefits – are we talking about food and water, or about beachfront developments? For some commenters, that would prompt different answers to those questions. A distinction was drawn between the needs of people in poorer countries and the wants of people in richer countries.

There is far more to unpick here, particularly given the complexity of the relationship between biodiversity and human benefits. There are many ways that biodiversity benefits us, whether it is the variety of wild pollinators of apple crops, or the diversity of birds I enjoy watching. Other aspects of biodiversity harm humans, with malarial parasites being an obvious example. Farmland will inevitably be less diverse than forest, but I do need to eat.

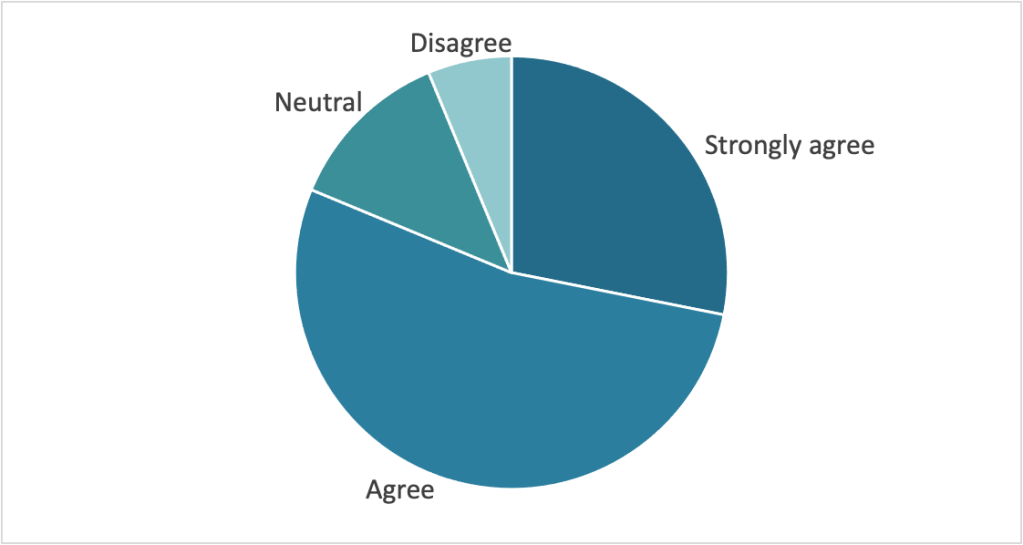

Animal welfare should be an important motivator for conservation

This question revealed a high level of support for animal welfare as a motivator for conservation; only 10% of respondents disagreed or strongly disagreed. This is in contrast to my experience of conservation – I seldom see animal welfare mentioned, and often see it dismissed.

Comments suggested that the impact of conservation activities on individual animals was seen as important, even if welfare isn’t a motivator for conservation. One commenter highlighted that welfare is critically important in situations where conservation impacts animals directly (such as in zoos), but we shouldn’t intervene in nature to reduce suffering.

One person associated animal welfare with food production and not conservation. Another felt that the welfare of wild animals was higher than the welfare of farmed animals.

Seeing support emerge early on in the survey, I added an extra question (which only later respondents had the chance to answer).

It is acceptable to kill introduced species (such as rats and cats) to protect native species

Despite the support for animal welfare in the previous question, there was overwhelming agreement that culling is acceptable.

In the comments, multiple people highlighted that removal of introduced species should be done humanely. One person felt that neutering is acceptable but not culling. One person expressed the belief that it is our responsibility to remove introduced species, given that we introduced them.

Trade-offs were highlighted when dealing with nature’s complex systems. Promoting the welfare of individuals of one species can affect other individuals – either of the same species or another species.

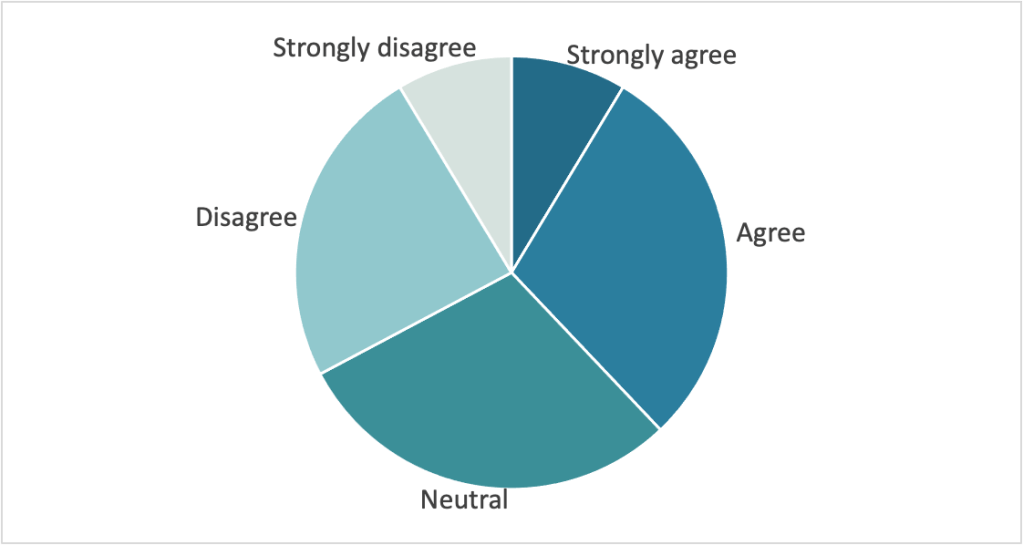

If an ecosystem is thriving, it doesn’t matter which species are part of it

This is the question that divided people the most, and many comments reflected the difficulty of the issue.

Multiple people stated the importance of prioritising native species, which implies that it does matter which species make up an ecosystem.

However, others disagreed. One person noted that species do and should evolve. Another person pointed out that humans have re-distributed so many species that it is probably impossible to undo the ecosystem changes. One person indicated that they were increasingly uncertain about this, given the need for species to move in response to climate change.

The importance of context was highlighted by some people – they may make different judgements depending on what form the ecosystem currently takes.

Again, some comments highlighted the need to define thriving. I intentionally left it vague, because this is a very tricky concept to define. Most people’s idea of thriving could include lots of individual organisms, lots of different types of organisms, and lots of active processes (such as pollination and decomposition).

The more an ecosystem has been altered by humans, the less valuable it is

Many comments spoke of human-altered ecosystems being important, but less-altered ecosystems being even more valuable.

There were lots of explanations of why human-altered ecosystems still had value. The UK has been completely altered by humans, and we value the ecosystems hugely. Dartmoor was highlighted as a specific example. Some species are doing better in urban areas, and gardens can be biodiverse. One person highlighted the joy they find in human-altered ecosystems, even though they prefer less altered ecosystems.

Some comments pointed out that conservation efforts can involve ecosystems being modified by humans. In these cases, ecosystems become more valuable when altered by humans (we hope). Seagrass restoration was given as an example.

Multiple comments suggested that change by humans isn’t inherently bad, but that many of the changes we’ve made are bad. Monocultures was an example.

One person highlighted that Indigenous peoples have been shaping landscapes long before western views of nature developed. Another person expressed the view that saying a human ecosystem is less valuable is “basically arguing for no change ever, which is inconceivable.”

As multiple people pointed out, what do we mean by valuable and who is it valuable to? One comment mentioned that we also need to ask what timescale we’re talking about: what’s valuable to some people in the short-term may undermine value in the long-term.

Harvest of wild plants/animals should be permitted wherever it is sustainable

This point had widespread agreement.

Points included that humans need resources to survive, and we need to coexist as part of nature. The importance of fair access was highlighted, including allowing Indigenous peoples to continue sustainable use of natural resources.

Multiple people felt more comfortable with harvest of plants than animals, and one comment pointed out that harvest of animals needs to avoid cruelty.

Some people expressed concern that, even though they agree with the statement in principle, harvesting can become unsustainable. Another comment highlighted the issue that we can define sustainability in different ways, and we need to use a definition that doesn’t compromise ecosystem functions.

One person agreed for subsistence, but suggested limitations for recreational harvest. On a similar note, one person highlighted the importance of distinguishing between needs and requests (behov och begär in Swedish).

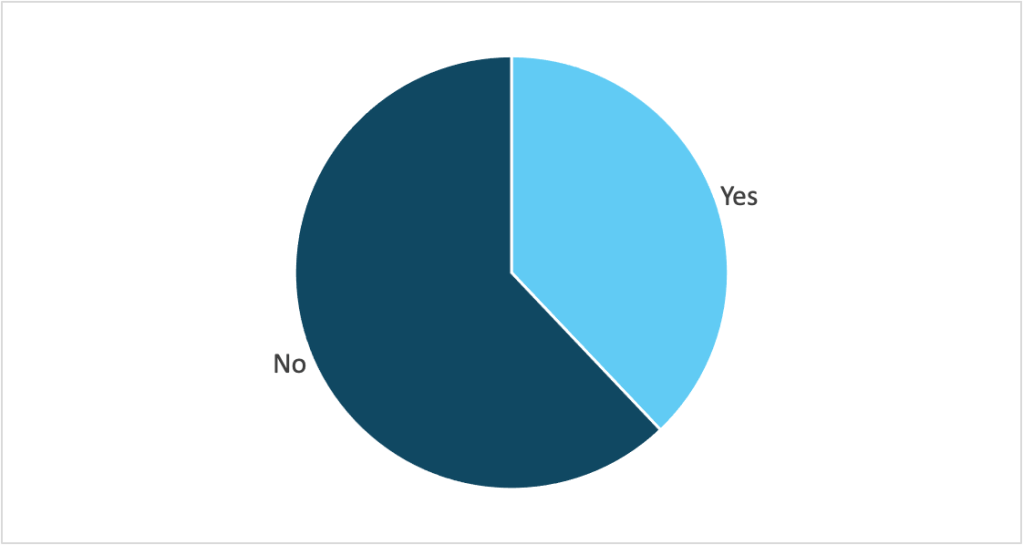

Have you explored the philosophy or religious teachings about the purpose of wildlife conservation?

Almost two thirds of respondents hadn’t explored the philosophy or religious teachings about the purpose of wildlife conservation. This was one of my motivations for writing Tickets for the Ark – I believe there is far too little discussion about these fundamental questions, and hope to spark some more debate.

A few people gave examples of what has influenced them. One person said Buddhism, multiple people mentioned Tickets for the Ark, and here is a list of the other books that were mentioned:

- Paul Colinvaux – The Fate of Nations

- Angus Martin – The Last Generation

- Blythe & Jepson – Rewilding

- Adam Hart – The Deadly Balance

- J. Howard Moore – The Universal Kinship

- Arne Naess – There is No Point of No Return

- Karen Armstrong – Sacred Nature

- Martha Nussbaum – Justice For Animals

- Alick Simmons – Treated Like Animals

- Hugh Warwick – Cull of the Wild

- Aldo Leopold – A Sand Country Almanac

- Mark Avery – Inglorious, & Reflection

- Guy Shrubshole – The Lost Rainforests of Britain

- Benedict McDonald – Rebirding

- Peter Singer – Animal Liberation

- Peter Mattheisen – The Birds of Heaven

- Jonathan S. Adams & Thomas O. McShane – The Myth of Wild Africa

Final comments

There were only a few responses to the open question inviting people to say anything else they wanted about protecting nature.

Some comments highlighted how bad the alternatives were, including climate change, species loss, pollution and, ultimately, an uninhabitable Earth. Multiple people spoke of the importance of protecting nature for their children. One person highlighted that we are very lucky to exist.

One person felt that that these questions are very simplistic on what is a complex subject. I agree, that’s a challenge of dealing with a diversity of views on such topics – you need enough simplicity to make sense of the conversation, but enough complexity that nuances are explored. I think one comment summed it up perfectly: “Tricky questions, you want to have a discussion around most of them.”

Roles and occupations of respondents